AbstractObjectivesThe study aimed to examine the effect of authentic parental competence and parental awareness of educational community on mothers’ life satisfaction and the magnitude of the direct and indirect effects of those variables. Given the increasing interest in parental life satisfaction, emphasis on parental involvement to educational community and its connection to the competence as a parent, there is much need to investigate the relationship among these in order to achieve a happy family via happy parents, the fundamental and ultimate goal of a society.

MethodsA non-clinical sample of 276 mothers of early childhood children in metropolitan areas of Korea completed Likert questionnaires. The age of participants ranged from 25 to 47 years, and the majority of participants were middle-class.

ResultsIn addition to the positive correlations among the variables, regression analyses indicated that authentic parental competence predicted maternal life satisfaction directly and indirectly via awareness of educational community.

ConclusionLife satisfaction of mothers of young children is not only directly affected by authentic parental competence, but also indirectly through the extent of how they aware their children’s education institutions as educational communities. This suggests the necessity to enhance awareness of early childhood education community as well as authentic parental competence in order to improve life satisfaction of mothers. Therefore, in early childhood education institutions and local communities it is required to implement parent education programs in order to increase authentic parental competence beyond parenting capability, and to make efforts together in establishing early childhood education institutions as educational community.

In the early years of parenthood, mothers make various efforts to be a good parent for the healthy development of their children. As a result, these mothers tend to discover desirable changes in their children and that increases their life satisfaction as a parent. On the other hand, some parents get stressed from childrearing, and parenting is the most important factor affecting quality of life and satisfaction of married women with young children (Ahlborg, Misvaer, & Möller, 2009; Bang, 2009; Jung & Lee, 2013). Given the rewards and burdens from parenting, it is essential to examine the underlying factors impacting on becoming a competent parent and determine how to effectively enhance those factors for an individual’s life satisfaction. Despite the great interest and commitment to parenting among early childhood parents (Anthony, Anthony, Glanville, Naiman, Waanders, & Shaffer, 2005; Belsky, 1984; J. Kim & Sung, 2014; Min, 2017; Ryan, Martin, & Brooks-Gunn, 2006; Seo, 2006), compared to job satisfaction (Do, Jeon, & Kim, 2012; Lee &Lee, 2014) or marital satisfaction (Ahn & Moon, 2017; J. J. Kim & Kim, 2008), not much investigation has gone into how the relevant parenting factors affect the overall quality of individual life of early childhood parents.

The competence as a parent seems to be related to his or her life satisfaction (Brock, Kochanska, O’Hara, & Grekin, 2015; Doherty, 2000; Guidubaldi & Cleminshaw, 1989; Lam, 1999). Given that competence can be defined in a variety of ways depending on context and purpose (Sansone & Morgan, 1992) and that today’s parents are suffering from depression and anxiety due to parenting stress and responsibility that deteriorate their quality of life (Nelson, Kushlev, & Lyubomirsky, 2014; Woods, 2005), parental competence, in general, is primarily regarded as parenting capacity. Parenting competence is the learned ability to effectively rear children by performing requisite tasks using demonstrable knowledge, skills, practices, attributes, attitudes, and compositions of these associated with positive outcomes in children (Johnson, Berdahl, Horne, Richter, & Walters, 2014; K. Kim & Han, 2018). Nevertheless, performing beyond and above parenting capacity is demanding for the parents. Therefore, parental competence can be considered as parental self-efficacy, coping skills, and the ability to cooperate with society as well as the parenting knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to overcome the multifaceted familial and social needs as Doherty (2000) suggested.

From the facts above, it can be stated that, in today’s society where we face various challenges and changes, the authentic competence for all parents who raise young children is the ability to maintain a high psychological well-being and to function adaptively as a member of a society, which is different from the conventional concept of parental competence used in a limited manner in earlier studies. Authentic parental competence, therefore, includes parenting competence related to knowledge, skills and attitudes required for childrearing, self-system competence required to maintain mental health including self-acceptance, affect regulation, and self-growth management, and social competence necessary to function socially well and to exert community spirit (K.-S. Chung & Choi, 2013; Rychen & Salganik, 2001). The study showed that the higher authentic parental competence the parents with young children had, the higher life satisfaction, the more positive emotions, and the higher level of self-efficacy as parents they experienced. Since high parental competence is related to positive and/or active attitudes and perceptions of childrearing and education (K.-S. Chung, Choi, Goh, & Park, 2014), it may encourage parents to actively collaborate with institutions and teachers to nurture their children in a good way and achieve desirable early childhood education. Despite this importance, there has not been active conduct of research to examine that authentic parental competence leads psychological wellness from satisfactory parenting experience, thereby affecting the overall quality of life as an individual.

Communities are groups of interdependent people who cooperate and collaborate, and human beings are characterized as social animals, forming and relating themselves to these communities. Thus the satisfaction or happiness of human life is influenced by community integration or social ties (Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, & Tipton, 1985; Demir, 2010). Schools have a major role in parents and children’s lives as a community. Specifically, school life is important for children’s sense of belonging and psychological well-being. Therefore, parents need to cooperate with the school based on their perception or judgment with a more objective standpoint on children’s well adjustment and happiness. School was found to be a major factor affecting the quality of life of children and families (Frisch, 2000), and it also explained the relationship between child’s environment and problem behavior (Huebner, Suldo, Smith, & Mcknight, 2004). Correspondingly, how the parents to perceive their children’s schools affects how they feel about their life.

Mothers’ perception on their engagement with school seems to affect their judgment on how well the early childhood education institutions their children attend are functioning. The recent findings suggest that when parents cooperate well with teachers, they will experience educational community characteristics of early childhood education institutions including mutual respect, trust, consideration, communication, and cooperation (K.-S. Chung & Noh, 2016). And the experience will have a positive impact on mothers’ perception of early childhood education institutions functioning as educational communities. More specifically, it is anticipated that maternal expectations of healthy schooling of their children will have a positive impact on maternal life satisfaction. In general, people with high personal competence are found to be highly satisfied, like how job competence predicts job satisfaction (J. Jung & Shin, 2015). Awareness of community is related to individual problem-solving abilities and coping strategies. Objective awareness of community will also be related to individual competence levels. If self-efficacy and sense of community level are high, the level of community participation increases by enhancing stress-coping ability in the community (Bachrach & Zautra, 1985). Therefore, it is assumed that authentic parental competence not only affects a mother’s life satisfaction directly but also indirectly through the awareness of early childhood education community. It was also supported that the authentic parental competence of a mother (i.e., parenting competence, self-system competence, and social competence) influences the perception of early childhood education community (K.-S. Chung, Yoon, Kyun, Cha, & Park, 2015) and life satisfaction of parents (K.-S. Chung & Kyun, 2014).

Parents often judge as to what extent their communal members share the core values of the school’s operation and how much companionship they have (K.-S. Chung, Kyun, & Park, 2015). Since early childhood education institutions are the first schools of their children’s lives, parents’ awareness of how well those institutions function as an educational community can affect their life satisfaction. In fact, the satisfaction level of life was high when non-employed mothers recognized that their organizations had a high degree of similarity of the core values and philosophies with their children’s early childhood education institutions (K.-S. Chung, Cha, & Moon, 2016). In Korea, however, there is virtually no research showing that the parental awareness of educational community is related to parental life satisfaction despite its impact on the increase of parental involvement. It needs to be examined whether parents are more satisfied with their lives as a parent when their objective perception of the school community is positive. This study, therefore, primarily explores the relationship between authentic parental competence and life satisfaction of early childhood mothers and tests whether the prediction of authentic parental competence on maternal life satisfaction is mediated by awareness of educational community. Specific hypotheses derived from the literature review were as follows:

First, what are the general perception of and the relations between authentic parental competence, awareness of educational community, and life satisfaction of mothers with young children?

Second, does awareness of educational community mediate the effect of authentic parental competence on life satisfaction of mothers with young children?

A survey was done among 283 mothers whose children were attending one of the five childcare or kindergartens engaged by acquaintances of the researchers. The authors provided explanations about the purposes of study and informed consents were collected from participants prior to the distribution of questionnaires. Among them, 276 mothers agreed to participate in research with 97.5% return rate. The age of participants ranged from 25 to 47 years, and 83.6% of the participants were 2-year college graduates at least, and 46.7% of the participants had jobs. Majority of the participants were middle-class having $20,000 (Statistics Korea, 2013) or above as their annual household income. The children enrolled either kindergarten for 49.6% or daycare for 47.1% (Table 1).

Satisfaction with life was measured using the three-item version of life satisfaction, which was developed as subscales of concise measure of subjective well-being by Suh and Koo (2011) and validated by K.-S. Chung, Park and Cha (2016). Satisfaction with life is measured in three different domains of life - personal, relational, and collective. The responder was asked to assess the following statements: (a) I am satisfied with the personal aspect of my life: (b) I am satisfied with the relational aspect of my life: and (c) I am satisfied with the groups I belong to. The items were rated on a 7 point Likert scale with the following response alternative (totally disagree[1]∼totally agree[7]), and summated scores were calculated. The possible range of scores is from 3 (low satisfaction) to 21 (high satisfaction). Higher scores on mothers’ satisfaction with life reflect that mothers are more satisfied with their lives. The reliability of the scale is well-established (Cronbach α = .88) and the internal consistency in this sample was fairly good (Cronbach α = .89).

Authentic parental competence was assessed using the concise version of early childhood authentic parental competence scale (K.-S. Chung et al., 2016). The scale was originally developed by K.-S. Chung and Choi (2013) based on the earlier studies on parental competence (Gilmore & Cuskelly, 2008; Holden & Hawk, 2003; Jones & Prinz, 2005; Kuczynski, 2003; Rychen & Salganik, 2001; Ryff, 1989; Turnbull & Turnbull, 1997) and validated by K.-S. Chung et al. (2016) later. This scale measures self-perception of parental competence that is required to perform a parental role. The scale consists of three factors of competencies (18 subfactors, 54 items) such as parenting competence (9 subfactors, 27 items), self-system competence (5 subfactors, 15 items), and social competence (4 subfactors, 12 items), having items asking knowledge, skill, and attitude per subfactor. Parenting competence refers to the ability of parents to adequately nurture and educate their children adapting to their developmental characteristics and needs. Self-system competence is the ability to maintain and develop psychological health through understanding and accepting themselves and their own happiness and is mainly based on the concept of psychological well-being. Social competence means the capacity to contribute to the development of individuals and communities as a citizen. Sample questions include “I have a lot of information about the learning method and content proper to the age of the child.” (parenting competence), “I know how to act independently without external demands or power.” (self-system competence), and “I live in cooperation with people in my daily life.” (social competence). Each item in a subfactor is rated very low (1 point) to very high (6 points) and each subfactor was represented by the average score of the sum of knowledge, skill, and attitude items. The higher the total score is, the higher the authentic parental competence is. The reliability (Cronbach α) is .97 for parenting competence

Awareness of educational community was assessed using the awareness of Korean educational community scale which was developed and validated by K.-S. Chung, Kyun, and Park (2015). The 5-point Likert scale consists of two dimensions: a sense of partnership (8 items) and a shared essential value (9 items). They were found to be the key factors in awareness of educational community in earlier literature (Cho & Seo, 2004; Redding, Murphy, & Sheley, 2011). The sense of partnership means that each member cooperates and voluntarily participates, cares, and devotes to the educational activities of early childhood education institutions. An example item is “Members have the attitude of mutual consideration and dedication.” The shared essential value means that members share the vision and direction of the early childhood education institutions including solidarity, seeking publicness, setting up an environment for participation and communication, and pursuing the identity of institutions. A sample item is “All members share essential value on education that the institution pursues.” Each item is rated on 5-point Likert-scale of not at all to very much agree and the score range is from 17 to 85, which means that the higher the score, the higher the degree of recognition of early childhood education institutions as educational communities. The reliability of the scale in this study was fairly good as .98 for the whole scale and .97 for partnership and shared essential value.

Both descriptive and partial correlation, path analyses were conducted using AMOS 23.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY), to test the direct and indirect effects of authentic parental competence on maternal life satisfaction and the mediating effect of awareness of educational community on the maternal life satisfaction. The path analysis results were expressed as the path of the regression coefficient, and p value and the significance of the effects were verified by bootstrapping (B = 1,000, 95% confidence interval, maximum likelihood method). Partial correlation and path analysis were conducted controlling for child’s sex, birth ranking, type of education institution, mother’s age, education level of mother, and household income. Listwise deletion removed all data for a case that has one or more missing values.

The descriptive statistics of the participants in terms of observed variables are shown in Table 2. The skewness and kurtosis showed that the data do not largely deviate from the normality regarding authentic parental competence, awareness of educational community, and maternal life satisfaction. Considering the midpoint score of each variable, the perception of authentic parental competence, awareness of educational community, and maternal life satisfaction of the subjects are high.

Correlation analysis shows the relationship among variable parameters (Table 3). Authentic parental competence was positively related to awareness of educational community (r = .23, p < .001) and maternal life satisfaction (r = .45, p < .001). Furthermore, awareness of educational community was positively associated with maternal life satisfaction (r = .33, p < .001). The significances were maintained after adjusting the control variables.

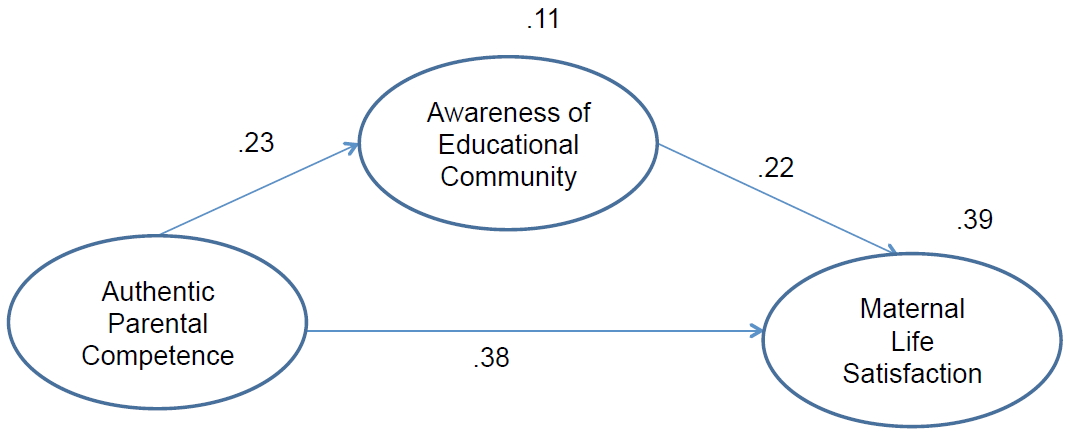

The Table 4 indicates the direct, indirect, and total effects of authentic parental competence and educational community awareness on maternal life satisfaction by bootstrapping (B = 1,000, 95% confidence intervals, MLE). The effect of authentic parental competence on maternal life satisfaction was partially mediated by awareness of educational community. In addition, the estimate of SMC in the partial mediation model with total effects explained 39% of the variation in the change in maternal life satisfaction (Figure 1).

Figure 1 presents the path pattern of the association of authentic parental competence and educational community awareness on maternal life satisfaction, and all of the hypothesized direct effects were significant. Authentic parental competence was positively related to the awareness of educational community (standardized β = .23, p = .002). Authentic parental competence had indirect effects (standardized β = .05, p = .002) as well as direct effects (standardized β = .38, p = .002) on maternal life satisfaction. Awareness of educational community was also positively associated with maternal life satisfaction (standardized β = .22, p = .002).

This study aims to investigate the effect of authentic parental competence and parental awareness of educational community on mothers’ life satisfaction and the magnitude of the direct and indirect effects of those variables. The results of this study are as follows.

First, the finding of significantly positive correlations among authentic parental competence, awareness of educational community, and life satisfaction of mothers with young children is consistent with the results of domestic studies targeting Korean mothers of young children (K.-S. Chung et al., 2014; K.-S. Chung & Noh, 2016; K.-S. Chung, Yoon, Kyun, & Park, 2015) support the findings by Bellah et al. (1985). In particular, the influence of developmental and positive parenting competence can be relatively large since young children are in most need of parenting. It also supports the argument (Deković, Asscher, Hermanns, Reitz, Prinzie, & van den Akker, 2010) that it serves as a mechanism to change parenting behaviors because parenting competence aims to increase the effectiveness of information sharing with teachers. The finding that mothers’ life satisfaction was related to their competence is consistent with previous research that parental self-efficacy increased resilience to negative emotion (Gilmore & Cuskelly, 2009) and mediated children’s problem behaviors and mothers’ mental health (Hastings & Brown, 2002).

Next, authentic parental competence predicted maternal life satisfaction directly and indirectly in association with awareness of educational community. Mothers’ parental competence predicted maternal life satisfaction directly, but that was partially mediated by awareness of early childhood education community. For a mother, subjective feeling or belief in her individual ability or participatory experience to institutional activities predicts satisfaction as mothers. And this impacts on awareness of educational community which is more likely to be regarded as objective expectation and evaluation. Therefore a mother becomes self-confident with her decision about the institution and that leads to satisfaction as a parent. The belief that sharing the philosophy or vision of an institution may positively affect the relationship between parents and teachers and ensure active involvement of parents in education communities. As its direct effect is larger than the indirect effect on maternal life satisfaction, authentic parental competence becomes more important ever. Therefore, creating an environment in which individual competence can be demonstrated is the key to happy motherhood. In particular, early childhood institutions and communities have focused on the implementation of parent education programs to enhance parenting competence (J.-M. Kim & Choi, 2018). More efforts need to be made to improve self-system and social competencies, which are other factors affecting authentic parental competence.

In conclusion, early childhood education institutions need actively encourage parents’ participation and maintain active communication between parents and teachers to enhance awareness of educational community. In order to do this, the parent should be fully aware of the effects of partnership with the teacher on the development and learning of the children and empower themselves by engaging in activities to learn and share specific skills and methods for better understanding and partnership with teachers. Communication with the teacher should be bidirectional so that the information, knowledge, and experience about the infant can be exchanged comfortably. The opportunity to have frequent contact with teachers also allows the parents to build a strong relationship with their teachers by having a good understanding of the teacher’s work and curriculum of the institution as Keyser (2006) suggested, and thus it can lead positive perception of educational community. Social practice such as stepping into the door makes for a substantial participatory action than theoretical justification about parental cooperation into school activities.

The present study contributed to acquiring knowledge on the effects of authentic parental competence and educational community awareness on life satisfaction of mothers with young children in addition to finding the relevance of these variables for the realization of an educational community.

Limitations of this study and research direction to supplement them it are as follows. This study was conducted only on mothers of a specific area, and thus a comparative study of the parents by including fathers is recommended. In addition, it is crucial to develop a tool that can collectively measure the communication between parents, teachers, and educational institutions to maintain the quality of education institutions and to accumulate relevant data necessary for community living. The results imply that it is necessary to objectively ensure the idea that the institution is good enough to make authentic parental competence bring life satisfaction in mothers. This could be a characteristic of Korean parents or a specific social class. Further research is required to examine the relationship between authentic parental competence, awareness of educational community, and life satisfaction of parents with diverse cultural and socio-economic backgrounds.

AcknowledgementsThis study was supported by the 2017 National Research Fund Korea (2017S1A3A2067778).

Figure 1Figure 1The associated effect of authentic parental competence and educational community awareness on maternal life satisfaction.

Table 1Descriptive Statistics of Teachers (Listwise N) Table 2Descriptive Statistics of Authentic Parental Competence, Awareness of Educational Community, and Maternal Life Satisfaction

Table 3Correlations Among Authentic Parental Competence, Awareness of Educational Community, and Maternal Life Satisfaction

Table 4Path Analysis for the Associated Effect of Authentic Parental Competence and Educational Community Awareness on Maternal Life Satisfaction

ReferencesAhlborg, T., Misvaer, N., & Möller, A. (2009). Perception of marital quality by parents with small children: A follow-up study when the firstborn is 4 years old. Journal of Family Nursing, 15(2), 237-263 doi:10.1177/1074840709334925.

Anthony, L. G., Anthony, B. J., Glanville, A. D., Naiman, D. Q., Waanders, C., & Shaffer, S. (2005). The relationships between parenting stress, parenting behaviour, and preschoolers’ social competence and behaviour problems in the classroom. Infant and Child Development, 14(2), 133-154 doi:10.1002/icd.385.

Bachrach, K. M., & Zautra, A. J. (1985). Coping with a community stressor: The threat of a hazardous waste facility. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 26(2), 127-141 doi:10.2307/2136602.

Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. M., Tipton, S. M. (1985). Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life with a new preface. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55(1), 83-96 doi:10.2307/1129836.

Brock, R. L., Kochanska, G., O’Hara, M. W., & Grekin, R. S. (2015). Life satisfaction moderates the effectiveness of a play-based parenting intervention in low-income mothers and toddlers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43:1283-1294 doi:10.1007/s10802-015-0014-y.

Deković, M., Asscher, J. J., Hermanns, J., Reitz, E., Prinzie, P., & van den Akker, A. L. (2010). Tracing changes in families who participated in the home-start parenting program: Parental sense of competence as mechanism of change. Prevention Science, 11:263-274 doi:10.1007/s11121-009-0166-5.

Demir, M. (2010). Close relationships and happiness among emerging adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11:293-313 doi:10.1007/s10902-009-9141-x.

Doherty, W. J. (2000). Take back your kids: Confident parenting in turbulent times. South Bend, IN: Sorin Books.

Frisch, M. B. (2000). Improving mental and physical health care through quality of life therapy and assessment. In E. Diener, & D. R. Rahtz (Eds.), Advances in quality of life theory and research (Social indicators research series. 4. (pp. 207-241). Berlin, Germany: Springer; doi:10.1007/978-94-011-4291-5_10.

Gilmore, L., & Cuskelly, M. (2008). Factor structure of the parenting sense of competence scale using a normative sample. Child: Care, Health, & Development, 35(1), 48-55 doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00867.x.

Guidubaldi, J., Cleminshaw, H. K. (1989). Development and validation of the cleminshaw-guidubaldi parent satisfaction scale. In M. J. Fine (Ed.), The second handbook of parent education: Contemporary perspectives educational psychology. (pp. 257-277). New York: Academic Press; doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-091820-4.50016-7.

Hastings, R. P., & Brown, T. (2002). Behavior problems of children with autism, parental self-efficacy, and mental health. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 107(3), 222-232 doi:10.1352/0895-8017(2002)107<0222:BPOCWA>2.0.CO;2.

Holden, G. W., Hawk, C. K. (2003). Meta-parenting in the journey of childrearing: A cognitive mechanism for change. In L. Kuczynski (Ed.), Handbook of dynamics in parent-child relations. (pp. 362-369). Thousand Oakland, CA: Sage Publishing; doi:10.4135/9781452229645.n10.

Huebner, E. S., Suldo, S. M., Smith, L. C., & McKnight, C. G. (2004). Life satisfaction in children and youth: Empirical foundations and implications for school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 41(1), 81-93 doi:10.1002/pits.10140.

Johnson, B. D., Berdahl, L. D., Horne, M., Richter, E. A., & Walters, M. (2014). A parenting competency model. Parenting: Science and Practice, 14(2), 92-120 doi:10.1080/15295192.2014.914361.

Jones, T. L., & Prinz, R. J. (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(3), 341-363 doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004.

Jung, J., & Shin, J. C. (2015). Administrative staff members’ job competency and their job satisfaction in a Korean research university. Studies in Higher Education, 40(5), 881-901 doi:10.1080/03075079.2013.865161.

Keyser, J. (2006). From parents to partners: Building a family-centered early childhood program. St. Paul, MN: RedLeaf Press.

Kuczynski, L. (2003). Beyond bidirectionality: Bilateral conceptual frameworks for understanding dynamics in parent-child relations. In L. Kuczynski (Ed.), Handbook of dynamics in parent-child relations. (pp. 1-24). Thousand Oakland, CA: Sage Publishing.

Lam, D. (1999). Parenting stress and anger: The Hong Kong experience. Child and Family Social Work, 4(4), 337-346 doi:10.1046/j.1365-2206.1999.00133.x.

Nelson, S. K., Kushlev, K., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). The pains and pleasures of parenting: When, why, and how is parenthood associated with more or less well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), 846-895 doi:10.1037/a0035444.

Redding, S., Murphy, M., Sheley, P. (2011). Handbook on family and community engagement. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Ryan, R. M., Martin, A., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2006). Is one good parent good enough? Patterns of mother and father parenting and child cognitive outcomes at 24 and 36 months. Parenting: Science and Practice, 6(2-3), 211-228 doi:10.1080/15295192.2006.9681306.

Rychen, D. S., Salganik, L. H. (2001). Definition and selection of competencies: Theoretical and conceptual foundations. Gottingen: Hogrefe and Huber.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069-1081 doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069.

Sansone, C., & Morgan, C. (1992). Intrinsic motivation and education: Competence in context. Motivation and Emotion, 16:249-270 doi:10.1007/BF00991654.

Turnbull, A. P., Turnbull, H. R. (1997). Families, professionals, and exceptionality: A special partnership(3rd ed.), Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

Woods, K. (2005). Examining the effect of medical risk, parental stress, and self-efficacy on parent behaviors and home environment of premature children. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Nebraska, Nebraska, USA.

Ahn, J.-S., & Moon, H.-L. (2017). Mediation effect of mothers’ parenting stress in the process that the marital relationship perceived by mothers affects the ego resilience of the children. Journal of Future Early Childhood Education, 24(1), 71-89 doi:10.22155/jfece.24.1.71.89.

Bang, H. J. (2009). Review of attachment theory and parenting. The Korean Journal of Woman Psychology, 14(1), 67-91 doi:10.18205/kpa.2009.14.1.004.

Cho, Y.-H., & Seo, G.-W. (2004). An ethnographic case study on the formation of communal education community. The Journal of Anthropology of Education, 7(1), 211-244.

Chung, K.-S., Cha, J. R., & Mun, J. A. (2016). The effects of authentic parental competence and awareness of the early childhood educational community on the life satisfaction of mothers with preschoolers: A comparison of employment status. Korean Journal of Child Studies, 37(6), 95-106 doi:10.5723/kjcs.2016.37.6.95.

Chung, K.-S., & Choi, E.-S. (2013). A study on the development of「 authentic parental competence scale」 for mothers with young children. The Journal of Korea Open Association for Early Childhood Education, 18(3), 225-257.

Chung, K.-S., Choi, E.-S., Goh, E.-K., & Park, H.-K. (2014). The relationship between parental competence and subjective well-being for mothers with young children when controlled by maternal employment status and household income. Korean Journal of Early Childhood Education, 34(2), 249-272 doi:10.18023/kjece.2014.34.2.012.

Chung, K.-S., & Kyun, J.-Y. (2014). The relationship of ‘authentic parental competence’ and parental efficacy in mothers of young children: Mediating effect of life satisfaction. Inmunhagnonchong [인문학논총], 35:113-143.

Chung, K.-S., Kyun, J. Y., & Park, H. K. (2015). Development of early childhood education community awareness scale: Targeting parents and teachers. Korean Journal of Early Childhood Education, 35(6), 95-116 doi:10.18023/kjece.2015.35.6.005.

Chung, K.-S., & Noh, J.-H. (2016). The effect of authentic parental competence and awareness of educational community on parent-teacher partnership among mothers with young children. Journal of Learner-Centered Curriculum and Instruction, 16(5), 713-736.

Chung, K.-S., Park, H.-K., & Cha, J.-R. (2016). A validation study of a short version of the authentic parental competence scale for mothers with young children. Korean Journal of Early Childhood Education, 36(2), 535-560 doi:10.18023/kjece.2016.36.2.023.

Chung, K.-S., Yoon, G.-J., Kyun, J.-Y., Cha, J.-R., & Park, H.-K. (2015). The figure and practical tasks of ‘warm’ early childhood educational community for recovering healthiness of early childhood education. Korean Journal of Early Childhood Education, 36(1), 153-182 doi:10.18023/kjece.2016.36.1.007.

Do, K. H., Jeon, G. Y., & Kim, S. K. (2012). The effects of occupational variables on parenting involvement and parenting satisfaction of the father with young children. Korea Journal of Child Care and Education, 73:443-458.

Jung, E., & Lee, M. (2013). The relationship between the difficulty of nurturing and the degree of life satisfaction of parents with infants: The mediating effect of couple communication and parental role satisfaction. Korean Journal of Family Welfare, 18(4), 485-510.

Kim, J., & Sung, J. (2014). The effects of mother’s parenting behavior style on individual differences in preschooler’s internalizing and externalizing behavior both at home and in preschool and teacher-child relationships. Journal of Early Childhood Education, 34(6), 391-410.

Kim, J., & Kim, Y. M. (2008). The effects of mother’s marital satisfaction influences on father’s parenting efficacy with general characteristics of one’s parents. The Korean Association of Child Care and Education, 54:269-287.

Kim, J.-M., & Choi, E.-A. (2018). Meta-analysis research on the trend of parent education program and self-system competency enhancement. Journal of Early Childhood Education & Educare Welfare, 22(2), 275-305 doi:10.22590/ecee.2018.22.2.275.

Kim, K., & Han, Y. (2018). A preliminary study on the development of parenting competence self-report scale for parents of infants. Korean Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 12(2), 29-53 doi:10.5718/kcep.2018.12.2.29.

Lee, H. S., & Lee, Y. N. (2014). The relationship between job satisfaction, parental role satisfaction, and the child rearing behavior of fathers of preschool children. Journal of Korean Child Care and Education, 10(2), 193-212 doi:10.14698/jkcce.2014.10.2.193.

Min, M. (2017). The effects of mother’s warmth parenting, control parenting, and self-esteem of preschoolers on the school readiness. Journal of Future Early Childhood Education, 24(4), 97-117 doi:10.22155/jfece.24.4.97.117.

Seo, S.-J. (2006). A study of children’s pro-social behavior: Children’s language development, requestive strategies, and maternal socialization beliefs and strategies. The Journal of Korea Open Association for Early Childhood Education, 11(4), 287-310.

Statistics Korea (2013). Household income & expenditure trends in the first quarter 2013. Retrieved from Statistics Korea website: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/index.action

.

Suh, E., & Koo, J. (2011). A concise measure of subjective wellbeing (COMOSWB): Scale development and validation. Korean Journal of Social and Personality Psychology, 25(1), 95-113 doi:10.21193/kjspp.2011.25.1.006.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||